The gaps criminals exploit: Why global AML collaboration is closer than you think

Criminals exploit gaps in both banks’ monitoring systems and also take advantage of jurisdictional gaps. Funds are routed through regulated entities with weak controls and monitoring, fragmented reporting frameworks, and cross-border channels.

Regulators are responding. Coordination efforts are now underway across FIUs, supranational bodies, and national authorities. FATF evaluations, bilateral MoUs, and the upcoming EU AML Authority all point to a more unified approach. But alignment on policy is only one piece. Effective collaboration depends on the ability to share intelligence securely, consistently, and without undermining local data control.

This blog examines how global AML frameworks are evolving, what makes cross-border cooperation so difficult in practice, and why infrastructure matters as much as regulation.

How criminals exploit fragmented regimes

Cross-border financial crime thrives on inconsistency. Criminals look for regulatory gaps, and the global system offers plenty. Differences in supervision, enforcement, and reporting standards between jurisdictions make it difficult to track activity from start to finish.

Many institutions have strong internal controls. But when one jurisdiction requires beneficial ownership disclosures and another doesn’t, or when intelligence-sharing protocols vary, it creates reliable blind spots. These inconsistencies are deliberately targeted, not as a last resort, but as a first step.

This is routine. Funds flow through offshore structures, nested correspondent accounts, high-risk PSPs, and crypto exchanges—often in combinations that cross regulatory lines. One institution might flag a transaction. The next may not. And without shared visibility, the risk is often missed or picked up too late.

Global AML efforts are only as effective as their weakest links. Fragmentation makes the system easier to navigate, for the wrong reasons.

Why regulators are finally closing ranks

Criminals have spent years exploiting the gaps between AML regimes. Now, regulators are responding. What was once fragmented and domestically focused is moving, deliberately, toward something more coordinated.

What’s driving it?

| Sanctions pressure is forcing cooperation | Loopholes in ownership disclosure and offshore structures have made sanctions enforcement patchy at best. The US, UK and other G7 countries are now fast-tracking MoUs to deal with crypto, offshore layering, and cross-border payment flows. |

| VASP oversight remain jurisdictionally fragmented and challenging | VASPs operate globally, but oversight doesn’t. Until regulators standardise supervision, criminals will keep exploiting uneven enforcement. |

| Offshore layering is still working far too well | Shell companies, nominee directors and multi-jurisdictional trust structures make it easy to break the audit trail. Disclosure thresholds vary widely and criminals plan for that. |

| Supervisors are under pressure to act system-wide | AMLA will directly oversee high-risk institutions across the EU by 2026. Egmont Group data-sharing is expanding. FATF evaluations are raising the bar. The message is clear: excuses based on jurisdictional scope are running out. |

| Capacity gaps are being targeted head-on | The FATF and UNODC are investing in regulatory infrastructure for weaker jurisdictions because global risk flows through the least prepared. |

Whereas these initiatives may have worked in isolation before, they’re now part of a broader development in how AML oversight is structured: less siloed, more coordinated, and increasingly intolerant of gaps that criminals depend on.

What cooperation looks like in practice

Global coordination is already underway. These changes go beyond policy, and they’re reshaping how AML is supervised and enforced. Investigations are moving faster. Typologies are being shared more widely. Supervisory models are starting to align.

Here are some recent developments shaping AML strategy:

EU AMLA

From 2026, the EU’s Anti-Money Laundering Authority will directly supervise high-risk institutions and enforce consistent standards across member states. This goes beyond guidance. It brings enforcement to the regional level.

Egmont Group

With over 160 FIUs connected, the Egmont Group is taking on a more active role in case coordination and typology development. It’s becoming an operational backbone for intelligence-sharing.

Bilateral MoUs

The US, UK, and other G7 jurisdictions are using bilateral agreements to coordinate on crypto risks, sanctions violations, and offshore flows. These agreements are built for speed and direct access, not bureaucracy.

FATF and UNODC capacity-building

These programmes are focused on jurisdictions that fall short of the FATF 40 Recommendations. Strengthening regulatory infrastructure in those regions is essential to reduce system-wide exposure.

Each of these initiatives addresses the same problem from a different angle: inconsistent oversight and slow collaboration. What’s changing is the expectation: faster coordination, better access, and fewer gaps to exploit.

What’s still in the way

Policy alignment is important, but it’s not enough. Even as regulators coordinate more closely, real-world cooperation is still limited by infrastructure, trust, and resourcing.

Some of the most persistent challenges include:

❌Systems don’t talk to each other

Many institutions and FIUs still rely on closed, outdated technology. They can’t exchange intelligence securely or train detection models collaboratively, even when they want to.

❌Cross-border data use is still a sticking point

Legal risk, institutional risk, reputational risk—too many actors default to isolation because data sharing feels too hard to manage. That stalls typology development and slows every investigation.

❌Uneven capabilities create soft targets

Some jurisdictions have mature supervision. Others don’t. That asymmetry gives criminals a roadmap, and they use it.

❌Inconsistent expectations for model governance

Supervisors want explainability. But when models are built in silos, everyone defines that differently. The result: reduced trust in any shared output.

Cooperation needs more than alignment. It needs shared infrastructure built for security, built for scale, and able to support a coordinated response to risk as it evolves.

Why change is harder than it looks

Despite growing momentum around collaboration, real progress remains slow. The benefits are well understood. The intent is clear. But several factors continue to hold the system back.

Data sharing still hits legal walls.

Cross-border intelligence sharing frequently encounters local data privacy laws. Even when the will exists, regulatory barriers make practical cooperation difficult.

Change is seen as risky.

In a field as sensitive as financial crime, change is often treated with caution. The risks of getting it wrong, operationally or reputationally, can outweigh the appetite to try something new.

Capacity is stretched.

Many institutions are consumed by day-to-day compliance. Building and scaling new models or frameworks often takes a backseat to clearing existing alerts or meeting urgent demands.

Outdated infrastructure slows progress.

Some jurisdictions still rely on legacy systems that weren’t built for 21st-century coordination. That makes collaboration harder, even when the intention is there.

Efforts like TMNL in the Netherlands show what’s possible when multiple institutions align. And initiatives like the Egmont Group could play a key role in accelerating change, if equipped with the right mandate and support. But for now, progress is uneven. Until infrastructure, governance, and trust catch up, truly global collaboration will remain an ambition rather than a norm.

What makes collaboration scalable

If global AML cooperation is going to work, it needs infrastructure built for it. Not more data pooling. Not more manual workarounds. Something that solves for collaboration, scale, and privacy at the same time.

That’s what Federated Learning delivers.

It gives institutions, regulators, and FIUs the ability to train models across multiple environments, without moving a single row of data. Models are trained locally, then combined into a shared intelligence layer. No raw data leaves the organisation. No sensitive information is exposed.

And it’s actively being used now. It works.

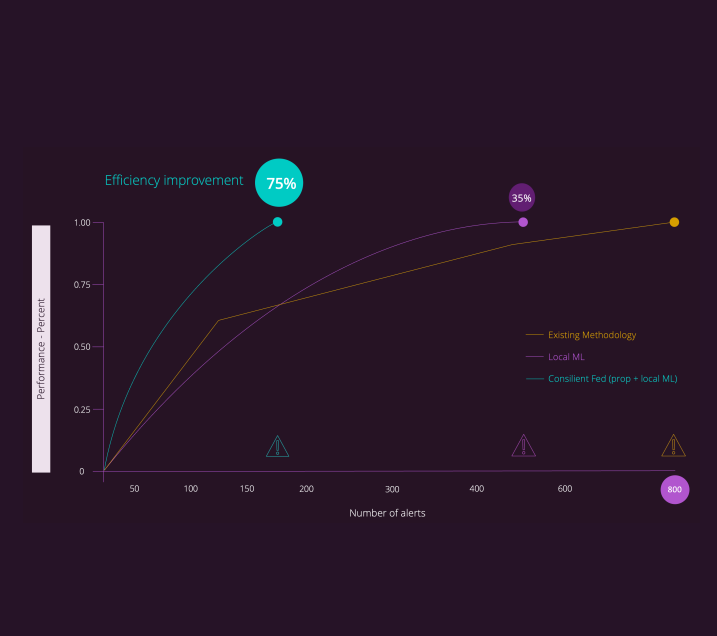

🟣One Tier-1 US bank saw a 75% increase in efficiency

🟣The same model delivered 4x the effectiveness of its existing system

🟣It flagged hidden risks that the institution’s local controls had missed

Consilient’s platform makes this possible. We provide pre-trained, explainable models that operate across regulated environments, with full privacy protection built in. Institutions keep control of their data. Supervisors get stronger results. Everyone sees the uplift.

For a sector that’s spent decades talking about collaboration, this is what it looks like in practice.

The infrastructure behind effective collaboration

The case for global alignment is no longer under discussion. It’s happening. But coordination only works if institutions and regulators have the infrastructure to support it, securely, consistently, and without delay.

Federated Learning makes that possible. It removes the trade-offs between privacy and performance. It enables shared learning without sharing data. And it delivers proven results where they matter most: detection, efficiency, and trust. See how it’s being applied inside banks, regulators, and FIUs today. Talk to Consilient about deploying Federated Learning.