Why smaller FIs face structural disadvantages in AML compliance

Smaller financial institutions face structural disadvantages in meeting anti-money laundering (AML) compliance expectations, despite being held to the same regulatory standards as larger firms. Regulators including FinCEN, the FCA (UK), the OCC, and the Federal Reserve, have acknowledged these challenges, which include limited access to advanced compliance technologies, constrained resources across critical functions, and difficulty attracting experienced personnel.

Smaller institutions must also balance AML obligations with competing business demands, often without the scale or infrastructure to deploy enterprise-grade controls. These barriers create significant operational pressure. Addressing this gap will require more scalable solutions, industry collaboration, and supervisory approaches that account for the realities of smaller institutions without compromising the integrity of the financial system.

In the past few years, smaller organizations such as community banks, neobanks, MSBs, crypto platforms, and gaming providers have become a growing priority for both financial criminals and regulators.

These firms often operate with far fewer resources, limited in-house expertise, unsophisticated technological approaches, and less developed compliance functions. Criminals see opportunity. Regulators see vulnerability. And the rest of the ecosystem is left exposed.

As enforcement extends beyond the headline-grabbing cases, supervisors are tightening expectations across the board. In this blog, we look at the challenges for smaller financial institutions, what it reveals about AML system design, and how technology can support a stronger, more resilient perimeter.

Why regulators are turning their attention to smaller firms

In recent years, smaller institutions with limited resources, smaller customer bases, and lighter-touch compliance functions have come under increasing scrutiny. That includes community banks, digital-first challengers, money services businesses, crypto platforms, and gaming providers.

Historically, regulators focused on large, complex institutions. But that focus is shifting. There’s now clear regulatory intent to ensure smaller institutions meet the same core AML obligations.

In October 2024, the OCC issued a Cease and Desist Order against Clear Fork Bank—a community bank with around $800 million in assets—for failing to implement a compliant AML program, monitor suspicious activity, and correct previously flagged issues. Despite its size, the bank faced significant supervisory demands, including SAR lookbacks, board-level compliance oversight, and enhanced reporting obligations.

The idea that only large institutions present meaningful risk has given way to a more comprehensive expectation: all regulated entities, regardless of size, must meet a baseline standard for AML effectiveness.

Why smaller financial institutions face structural disadvantages in AML compliance

Regulators in both the United States and the United Kingdom expect all financial institutions to maintain effective anti-money laundering (AML) programs. However, smaller banks, credit unions, fintechs, and non-bank financial institutions often face structural disadvantages that make this mandate disproportionately difficult. Agencies such as FinCEN, FCA, the Federal Reserve, and the OCC have increasingly recognized the unique pressures facing these institutions, even as expectations around compliance continue to rise.

1. Sustainability versus the cost of compliance

Smaller institutions operate with tighter margins and a greater focus on financial sustainability. For many, AML compliance is not revenue-generating but instead represents a growing cost that must be absorbed. This trade-off becomes especially stark in lower-value, high-volume sectors such as remittances, prepaid cards, or community banking. Unlike large global banks, smaller firms cannot easily spread compliance costs across broad portfolios, making it harder to keep pace with evolving regulatory requirements.

2. Limited access to the best solutions

Top-tier AML technologies, such as advanced transaction monitoring systems, real-time risk scoring engines, and AI-enhanced screening tools, are often priced beyond the reach of smaller institutions. FinCEN has emphasized the importance of risk-based programs that are scalable and effective, but this still assumes a baseline investment in technology. Smaller firms may be forced to rely on manual processes, outdated systems, or low-capability vendors, all of which increase operational risk and the likelihood of control breakdowns.

3. Resource constraints across all functions

Running a financial institution requires oversight of far more than just financial crime risk. Smaller firms must also manage cybersecurity, liquidity, data privacy, customer protection, and regulatory reporting, all often with limited headcount and infrastructure. Large institutions operate with specialized teams across compliance, risk, and audit. Smaller entities may rely on dual-hatted roles, thin second-line functions, or outsourced services, reducing their ability to proactively manage AML obligations.

4. Gaps in technical capability and experience

Recruiting and retaining experienced compliance professionals remains a major challenge for smaller institutions. Larger banks and global financial firms can attract seasoned AML officers with deep domain knowledge. Smaller firms, particularly in rural or early-stage environments, may struggle to compete. The OCC and Federal Reserve have noted that weaker institutions often fall short not due to lack of effort, but due to insufficient internal expertise resulting in incomplete risk assessments, inadequate customer due diligence, and poorly structured alert triage.

5. Challenges in embedding a compliance culture

Establishing a culture of compliance is foundational to effective AML controls. However, in smaller or growth-stage firms, this culture can be overshadowed by commercial pressures, aggressive targets, or limited board engagement. Regulators such as FinCEN, FCA (UK) and the OCC have repeatedly stressed the importance of tone from the top. Without clear leadership, dedicated resources, and internal challenge, smaller institutions may deprioritize compliance or inadvertently accept higher-risk customers or behaviors to sustain growth.

Regulatory acknowledgment and expectation

US regulators increasingly understand the operational constraints faced by smaller institutions. FinCEN’s outreach to community banks, credit unions, and money services businesses has acknowledged these barriers. However, this recognition does not lessen the regulatory expectations. Programs must still be risk-based, well-documented, and demonstrably effective. As enforcement actions have shown, size does not exempt firms from their obligations.

Why smaller firms are vulnerable and why they’re attractive to criminals

Smaller financial institutions often operate with structural disadvantages that make them easier to target and harder to supervise. These weaknesses aren’t isolated; they create knock-on effects across the financial system.

Key vulnerabilities include:

➡Underdeveloped customer due diligence (CDD)

Many smaller firms rely on simplified onboarding processes, particularly when dealing with fast-moving or underserved customer segments such as gig workers, migrants, and crypto users. Risk scoring at the point of onboarding is often static and rules-based, with limited ability to detect behavioural red flags.

➡Limited transaction monitoring and risk detection

Real-time monitoring, behavioural analytics, and contextual alerting are often missing or underused. These blind spots create space for micro-layering, structuring, and other techniques that help criminals avoid detection.

➡Inadequate governance and resourcing

These firms often lack the compliance expertise, governance structures, and internal controls that larger institutions take for granted. They’re slower to identify emerging typologies, less able to tune detection systems, and more exposed when regulators come calling.

➡Exposure to higher-risk or underserved populations

Smaller institutions often serve customers who are excluded from mainstream banking. While this supports financial inclusion, it also introduces AML complexity—thin credit files, unclear source of funds, and limited identity data all make risk assessment harder.

➡Less monitored transaction channels

Payment services, MSBs, and gaming platforms often provide pathways that sit outside traditional scrutiny. These flows are frequently used to layer illicit funds before they reach larger institutions.

Criminal networks use these weaknesses to:

🟣Open mule accounts across poorly supervised providers

🟣Move funds through small, repeated transfers that avoid detection thresholds

🟣Onboard high-risk customers at the edge of the system, before routing funds to more regulated destinations

And these create points of entry for illicit finance across the financial system. Risk doesn’t stay local, and regulators are no longer prepared to overlook that.

When risk enters the system, it doesn’t stay contained

Illicit financial activity doesn’t stay contained once it enters the system. A weak onboarding process at a local bank, fintech or payments firm can provide the entry point for bad actors. Once inside, illicit funds can flow seamlessly through payment networks, correspondent banks, or transfers into larger institutions, obscuring their origin in the process.

The concern goes beyond missed alerts or inconsistent controls. Smaller firms can become systemic access points for activity that would be blocked elsewhere. By the time the transactions reach a well-defended institution, the original source is hard to trace, and the exposure is more difficult to address.

This is driving a broader regulatory response. Supervisors are no longer satisfied with strong compliance only at the top. They expect minimum AML standards to be met across the entire system. It’s not just about detecting risk at the final destination. It’s about preventing it from entering the system in the first place.

Regulators are closing the gaps

Regulatory action has expanded well beyond the largest banks. Enforcement now targets the points in the system where controls are weakest and where financial crime is most likely to take hold.

Recent developments include:

FATF’s 2023 Risk-Based Guidance:The Financial Action Task Force called out under-supervised sectors such as casinos, MSBs, and high-value dealers. These channels are widely used for initial placement and early-stage layering of illicit funds.

FinCEN’s enforcement against smaller MSBs and fintechs: U.S. regulators have taken a firm stance on institutions lacking effective AML frameworks, particularly those facilitating high-risk payments or crypto transactions.

FCA penalties for mid-sized and challenger banks: In the UK, firms like Metro Bank and Starling have faced public penalties for AML failings that, in previous years, may have received only private warnings. That discretion is no longer the norm.

These interventions reflect a clear tightening of expectations.

Smaller institutions are no longer treated as exceptions. They are expected to meet the same fundamental requirements as larger peers, especially when their services connect directly into the broader financial system.

For firms operating in sectors previously considered out of scope or low priority, this is a big change. Every participant has a role in strengthening the AML perimeter, and gaps are no longer likely to be overlooked.

What this means for larger institutions

The risks facing smaller firms don’t stay contained at their level. When compliance fails at the edge of the system, exposure is passed upstream to correspondent banks, payment networks, and global institutions that rely on those flows.

This creates both operational and reputational risk for larger firms. In many cases, they inherit the consequences of poor controls elsewhere: delayed investigations, misaligned alerts, or sanctions breaches that originate from outside their direct oversight.

Larger institutions are also expected to manage not just their own controls, but also the exposure introduced through partners, channels, and ecosystem relationships. Here’s how this expectation is shaping compliance strategy:

🔵Reassessing reliance models used for smaller banks, fintechs, and MSBs

🔵Reviewing onboarding and transaction flows linked to third-party providers

🔵Participating in collaborative efforts to strengthen AML detection across the network

The regulatory focus has moved from isolated compliance to collective resilience. Larger institutions have both the visibility and the capability to lead that effort.

How Federated Learning can help close the gap

Smaller institutions are often held back by constraints they can’t easily fix: limited resources, fragmented systems, and a lack of in-house data science. And they’re not alone. It’s a systemic risk and it’s growing.

That’s where Federated Learning steps in.

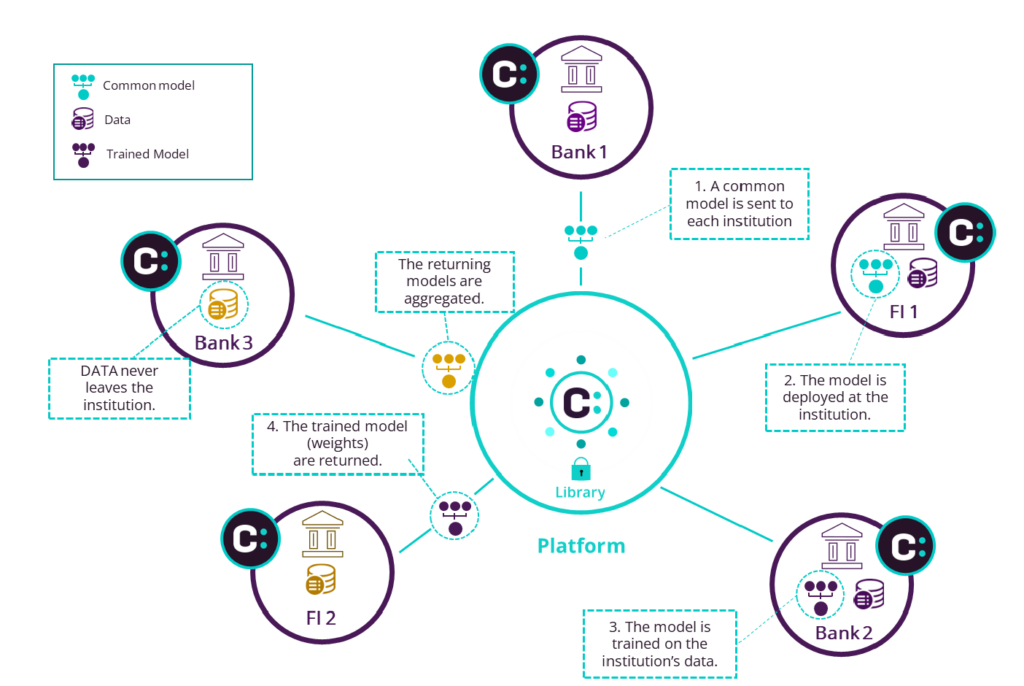

Federated Machine Learning offers a smarter way to strengthen AML performance across the board. It allows institutions to collaborate to train and deploy advanced risk models without sharing data. Intelligence is drawn from a network of contributors, not a single institution.

That means smaller institutions can leverage the power and resources larger organizations can deploy to detect illicit activity, securely and privately. Federated Learning provides smaller companies better detection, fewer false positives, and stronger early warning, especially where traditional rules-based systems fall short.

Consilient is driving this change. Our solution brings together financial institutions of all sizes to benefit from shared model intelligence, without ever pooling sensitive data. We give firms access to:

✅Pre-trained, explainable risk scoring models

✅Intelligence shaped by multiple real-world environments

✅Deployment options that meet strict regulatory and operational requirements

Banks are already seeing the benefits. It’s being used to raise the baseline for AML across diverse financial institutions. Whether you’re operating with limited internal capacity or managing complex third-party exposure, Federated Learning delivers uplift where it’s needed most, and Consilient helps you make it real.

| Consilient’s AML FL models have delivered up to 4x greater detection effectiveness and a 75% improvement in efficiency, without requiring institutions to share data. ➡Learn more about how it works in practice. |

Building AML resilience across FS & banking

Financial crime doesn’t respect institutional boundaries, and neither should the defences against it. As regulators push for stronger, system-wide resilience, the perimeter is expanding and expectations are rising. That means every institution has a role to play, regardless of size.

With the right technology and the right approach, the sector can respond. Federated Learning offers a way to close capability gaps, reduce shared exposure, and strengthen AML where it will have the most significant impact. Consilient is helping financial institutions do exactly that. Looking to strengthen AML across your network? Talk to Consilient about how Federated Learning can help your institution reduce shared exposure, support ecosystem-wide resilience, and stay ahead of rising regulatory expectations… All without sharing sensitive data.