Human in the loop in 2026: What AML governance now needs to evidence

This is not another recap of why “human in the loop” is crucial.

It is an examination of how that concept is actually tested in today’s AML systems, and why many governance frameworks no longer align with how decisions are made in production.

Most AML decisions now happen before a human ever sees them. Risk is scored, thresholds applied, and routing decisions are made in real time. By the time an alert reaches an analyst, the outcome has already been shaped.

Governance frameworks still place “human in the loop” at the center of control, even as most control now executes before humans can intervene. In practice, that loop often sits downstream of automated decisioning, supporting review, challenge, and assurance rather than real-time intervention.

You can see this play out in supervisory reviews. Examiners ask who approved a decision, when escalation occurred, and what evidence shows the control operated as designed. In high-velocity AML environments, those answers increasingly live inside model logic, escalation rules, and operational configuration.

That’s why “human in the loop” is under renewed scrutiny in 2026.

| This blog covers: 🟣What “human in the loop” actually means in modern AML systems 🟣Why real-time decisioning challenges traditional governance assumptions 🟣How examiners assess accountability when decisions are automated 🟣Where escalation logic functions as a control mechanism 🟣What AML governance needs to evidence in 2026 supervisory reviews |

The human-in-the-loop stack

Let’s kick things off with a simple way to think about this.

When examiners talk about “human in the loop,” they’re really asking how decisions flow from data to action, and where accountability sits along that path.

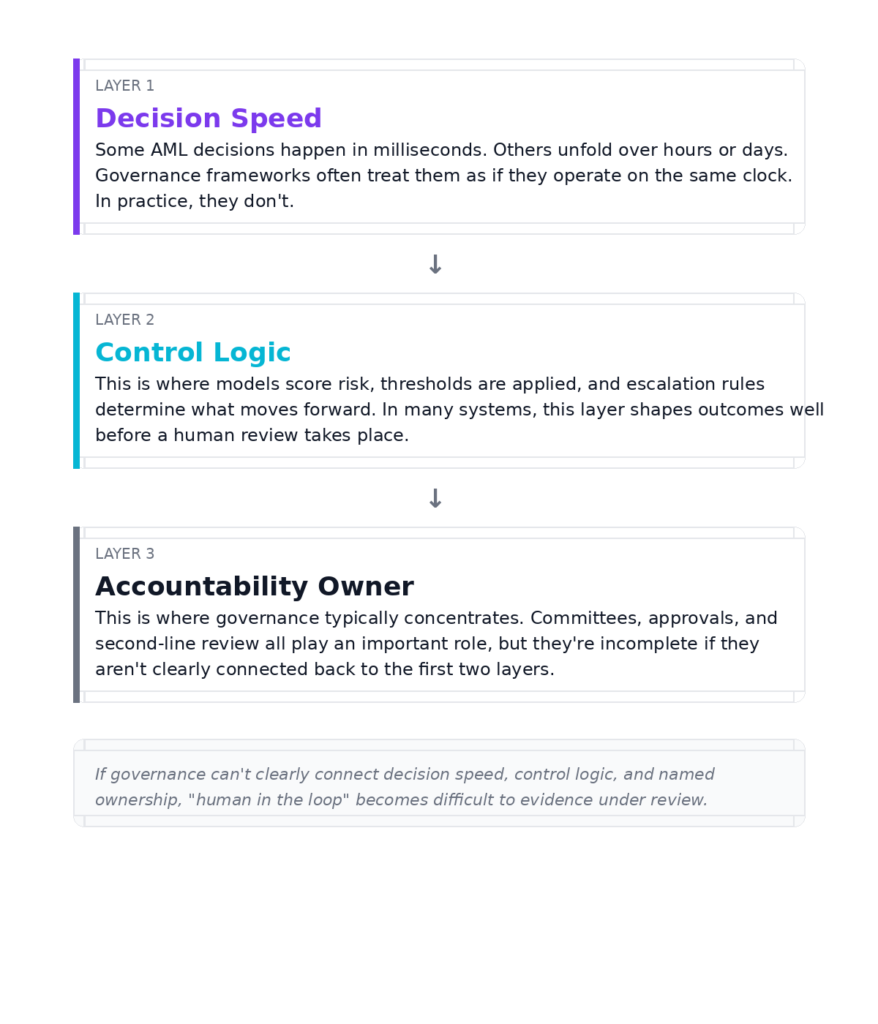

I find it useful to think about this as a three-layer stack:

- Layer one: decision speed.

Some AML decisions happen in milliseconds. Others unfold over hours or days. Governance frameworks often treat them as if they operate on the same clock. In practice, they don’t. - Layer two: control points.

This is where models score risk, thresholds are applied, and escalation rules determine what moves forward. In many systems, this layer determines outcomes well before a human review takes place. - Layer three: accountability.

This is where governance comes in. Committees, approvals, and second-line review all play an important role, but they’re incomplete if they aren’t clearly connected back to the first two layers.

You can see the issue here. Governance tends to describe layer three in detail, while supervisory reviews increasingly focus on how layers one and two operate in production.

The takeaway: If governance can’t clearly connect decision speed, control logic, and named ownership, “human in the loop” becomes difficult to evidence under review.

#1: “Human in the loop” is a timing problem

Most governance frameworks describe who is responsible. They spend far less time specifying when that responsibility applies.

In AML systems operating at scale, timing matters. Transaction monitoring, interdiction, alert suppression, and prioritization often happen in seconds. Human review processes typically sit outside that window.

You can see the issue here. Policies often assume a human can intervene at the point of decision. In practice, the system applies logic first and presents a narrowed set of outcomes for review later.

Here are two examples.

First, alerts that never surface because suppression logic determines the risk is low enough to bypass review. Second, higher-risk activity routed into queues where review occurs days, and sometimes weeks, after the behaviour took place.

In both cases, automated logic has already shaped exposure before a person becomes involved.

The takeaway: Governance needs to specify when (and why) human involvement occurs in relation to the decision, not simply state that it exists somewhere in the process.

#2: Escalation logic has become the real control

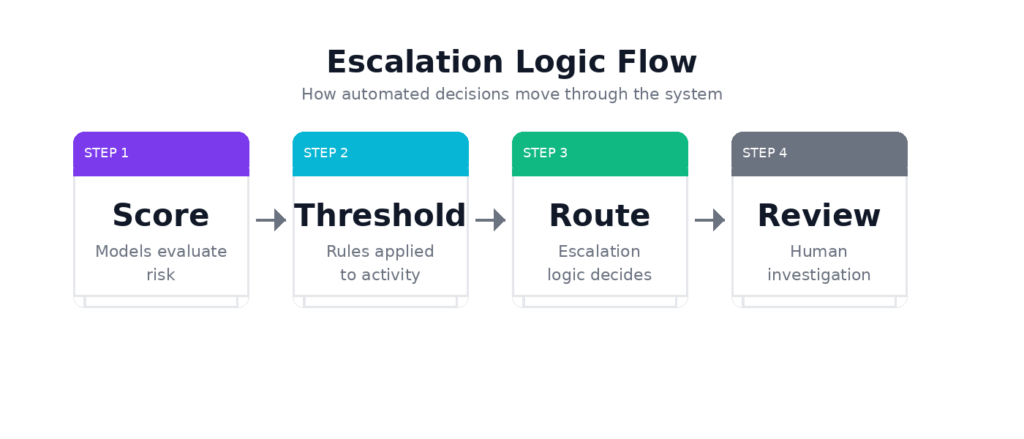

As decisions move closer to real time, escalation rules start carrying much of the control load.

Models score activity, but thresholds and routing logic determine what gets attention, what gets delayed, and what never enters review. Those choices determine how compliance effort is deployed across the system.

Banks have taken a bunch of steps to formalize escalation in policy. But it’s not enough, and we need to do more because examiners increasingly focus on how alerts move through the system. They want to understand why something escalated, why something didn’t, and who approved the rules that governed those outcomes.

Consider alert queues ranked by model confidence. A small threshold adjustment can significantly change review volumes. And the governance impact often only becomes clear after it has been deployed.

The takeaway: Escalation logic needs to be treated as a governed control, with clear ownership and change evidence, rather than as a purely technical implementation detail.

#3: Accountability needs a name, not a committee

In supervisory reviews, accountability is tested down to the level of individual decisions, and not just organisational intent.

The problem is that most AML frameworks assign accountability through committees, working groups, or layered sign-offs. They’re great for setting the direction, approving models, and providing challenge. But they’re less effective at answering questions about decisions made continuously in production.

Of course, this can be hard to do in practice, especially in large institutions. When responsibility for models, thresholds, and routing logic is spread across teams, accountability actually can become shared by default. Shared accountability is difficult to evidence when examiners ask who had authority over a specific decision at a specific point in time.

Even when outcomes are acceptable, the shared accountability becomes difficult to evidence. Committees approve frameworks and policies, but they do not execute decisions. And because of this, ownership at execution time is often assumed rather than formally documented.

This is where some banks are starting to introduce more explicit approaches, such as a decision authority ledger. For each system, it sets out:

- ➡what decisions the system is authorised to make

- ➡the boundaries within which it can act

- ➡when escalation is required

- ➡who owns those boundaries

- ➡what evidence is captured at execution time

The takeaway: Governance travels better through examinations when accountability for automated decisions is explicit, named, and tied to defined decision boundaries, rather than implied through forum structures alone.

#4: Evidence beats intention in model reviews

Most AML programs can clearly explain how governance is designed to work. The challenge comes when examiners ask to see what actually happened at the moment a decision was executed.

The challenge is that banks can describe oversight structures and approval processes in detail, yet struggle to reconstruct individual decisions months later.

In stronger programs, preserved decision evidence tends to include four elements:

- ➡the input data captured at decision time

- ➡the boundary or rule that applied

- ➡the threshold that triggered the action

- ➡the named owner who approved that boundary

Combined, those elements allow a decision to be reconstructed and defended long after it occurred.

Having said that, even when those controls exist, examiners still probe whether they operated as designed in production, not just whether they were reviewed after the fact.

The takeaway: governance becomes far more defensible when decision evidence captures not just what happened, but why it was allowed to happen, and under whose authority.

Where federated models support governance and evidence

The practical challenge in all of this is scale. How do you strengthen decision evidence without adding manual steps or slowing systems that already operate in real time?

This is where federated learning becomes even more useful from a governance perspective.

Federated models allow banks to learn from laundering patterns observed across multiple institutions, without sharing customer data. That broader context helps risk teams move away from purely local data and towards behaviour that is known to matter at a network level.

They can be tied to specific typologies, used consistently in alert prioritization, and referenced in escalation thresholds that have been approved in advance.

So, instead of relying on post-hoc interpretation, banks can demonstrate how an alert ranked relative to patterns seen across the network at the time the decision was made. This strengthens model validation or oversight by embedding context into the decision itself, making it easier to evidence why certain activity was prioritized, escalated, or deprioritized.

The takeaway: Federated learning helps align governance intent with operational execution by providing consistent, network-level context that can be used as decision evidence at runtime.

What good AML looks like in 2026

By 2026, stronger AML programs will be defined by tighter alignment between governance intent and operational execution.

- 🟣First, autonomous decisioning is made visible early. Systems capable of acting without human intervention are explicitly identified, rather than discovered during validation or examination.

- 🟣Second, decision boundaries are defined in advance. For each automated decision, there is clarity on what the system is allowed to do, when it must escalate, and where human accountability sits. Those boundaries are approved before deployment and revisited when risk appetite changes.

- 🟣Third, escalation logic is governed as a control. Thresholds, routing rules, and prioritization logic have named owners and clear change records. Adjustments are reviewed for both operational and risk impact.

- 🟣Fourth, decision evidence is preserved at execution time. Inputs, applied rules, thresholds, and accountable owners are captured as decisions are made, allowing activity to be reconstructed months later without relying on interpretation or memory.

- 🟣Finally, oversight connects back to production. Model review, second-line challenge, and QA testing focus on whether approved boundaries and escalation rules are operating as intended in live environments, not just whether policies exist.

Taken together, these practices allow automation to scale while keeping accountability clear and defensible.

The takeaway: In 2026, effective AML governance is about ensuring existing AML controls are enforced, evidenced, and auditable where decisions are made.

Final thoughts

By 2026, the key requirement is demonstrating that intent is visible exactly where real-time decisions are executed, meaning governance must now operate at the speed of your models.

The next step: Ask your AML and model risk teams to identify which automated decisions would benefit from network-level insight. Federated learning can help ground those decisions in broader laundering patterns without sharing sensitive data. Talk to us. We’d genuinely love to help.